BILL Bruford has a curious relationship with his first band, Yes – one which, in part, seems to reflect his rather mixed feelings about rock music generally, plus his experience of jazz as a quite different approach to music – a point which I will return to in more detail later in this article.

BILL Bruford has a curious relationship with his first band, Yes – one which, in part, seems to reflect his rather mixed feelings about rock music generally, plus his experience of jazz as a quite different approach to music – a point which I will return to in more detail later in this article.

But let’s start with Yes. On the positive side, Bruford is evidently grateful to the band for providing his formative experience and early wings in music. He is notably proud of the 1972 album ‘Close to the Edge’, which is widely considered the group’s greatest achievement – certainly with him on board. That said, it took ages to create, and the recording proved enormously frustrating for Bill, so that his move to King Crimson, and a more instrumentally adventurous and improvisational musical context, proved a relief (albeit in another demanding, fragile, difficult set-up).

The early albums (‘Yes’ and ‘Time and a Word’) Bruford has dubbed “naïve”, if contextually creative, efforts. Similarly, that is how he describes his first solo writing credit – the succinct “Five Percent for Nothing” on ‘Fragile’, which also ended up being seen – unfairly in my view – as something of a filler. The tune “Heart of the Sunrise”, from ‘Fragile’, features in his book When In Doubt, Roll! (Modern Drummer, 1998, republished in 2012 by Foruli Classics), which is a compendium featuring 18 of Bruford’s recorded works in notated form, together with some scene-setting and explanation as to how and why he arrived at the end result. In that context he references that ’70s progressive rock style as having validity for its time. But clearly it was never a destination for him.

Bruford has also described Yes as “like a first girlfriend” – a relationship which sets you out on the path of learning how to form essential bonds, while falling short of a more serious encounter, or a marriage. The analogy could be stretched in a number of directions to describe both the affections and limitations of the Bruford-Yes connection, its fun times and its fury. His frustrations with the late, slow, limited output, heavy consuming (of time, money and substances) Chris Squire are well recorded, for instance. Then again, he paid fulsome, considered tribute to the late bassist’s talents and individuality after his death in 2015, describing those melodic, counterpointed basslines as “little stand-alone works of art in themselves”, and later joining others at a moving memorial service for Squire in London.

Bruford has also described Yes as “like a first girlfriend” – a relationship which sets you out on the path of learning how to form essential bonds, while falling short of a more serious encounter, or a marriage. The analogy could be stretched in a number of directions to describe both the affections and limitations of the Bruford-Yes connection, its fun times and its fury. His frustrations with the late, slow, limited output, heavy consuming (of time, money and substances) Chris Squire are well recorded, for instance. Then again, he paid fulsome, considered tribute to the late bassist’s talents and individuality after his death in 2015, describing those melodic, counterpointed basslines as “little stand-alone works of art in themselves”, and later joining others at a moving memorial service for Squire in London.

Again, Bruford often referenced his general lack of nostalgia for the musical past during the course of his performing years (though he has recently been involved in carefully curating his various collaborations through his Winterfold and Summerfold labels). For him, particularly when his career moved irreversibly to jazz – with the second, acoustic incarnation of Earthworks – what gets called ‘prog’ seems a largely backward-looking phenomenon, fatally restrained by rock culture and habits. Something that is fine for its particular moment in history, perhaps, but mostly (with exceptions like Robert Fripp and Steven Wilson, who get cast into this category) not a space where new ideas and possibilities can be explored readily. Likewise, if you want to know about drumming as an adventurous and expressive art form, you look to jazz, not to rock, he suggests.

ABWH and the Yes re-union tour

So while the erstwhile Yes drummer saw fleeting moments of musical possibility with Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe (especially with a track like “Birthright” on the eponymous 1989 album), he was frustrated that management and the record company soon closed that down, because their interest was in commercial success far before any concern for music. As he puts it:

For about two or three months it seemed as if Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe really had a group in the making. It seemed as though we would establish a body of work and eventually evolve away from the Yes material. However, the politicians got involved and that idea was quickly crushed. (quoted in ‘Bill Bruford: Splashing Out’, by Anil Prasad, Innerviews, 1992.)

Then again, from a pragmatic point of view:

There’s no doubt that Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe and Yes have turned into a financial bonanza for me, which is absolutely great. There’s no musical future in it from my point of view – it’s regressive music, it’s historical stuff. But once in a while, I think a musician is allowed to go on vacation and make everyone very happy by playing all the stuff they all want them to play from 20 years ago. But it’s nothing that I would give up my day job for, which I know very well is to play music that you don’t know that you want yet, but you will want it in 10 years’ time. (Innerviews, ibid.)

Then there is the collapsing of ABWH into a many-tentacled Yes octopus. The 1990-1992 ‘Union’ Yes was an artificial product which produced an elaborately concocted recording at vast expense, necessitating a nostalgia-drenched “around the world in 180 dates” tour in which most of the new material was not played. In some respects Bruford has spoken warmly of that tour (though he is excoriatingly dismissive of the album, which I try to look at in a rather different light in Solid Mental Grace: Listening to the Music of Yes, pages 122-125). The Union Tour was, he suggests, an opportunity to reconnect with old friends in a relatively congenial musical environment, to please many thousands of fans, and during the course of what was effectively intended as a long summer break for him, to bankroll a significant sum of money to invest in his real love, Earthworks, and similar projects.

On the other hand, he clearly found the repetitiveness of having to play the same parts night after night frustrating. Repetition is a major sin in the Bruford musical lexicon – understandably so. His philosophy is “Never the Same Way Once” (Earthworks, with a title that may be referencing Doc & Merle Watson). Band politics spilling over into performance compromises was probably also an irritant, and while he and fellow-drummer Alan White got on well enough personally, they are miles apart style-wise. Their mid-way solo slot offered only limited opportunities for variation, and Bill felt that he was, metaphorically, adding Hollandaise sauce to White’s meat and potatoes (he often quotes a review which puts it exactly that way.) So he saw his role as fairly superfluous in a rather inflated live mix. The complete breakdown of his electronic drums at one point on the US leg of the tour was also a sore point – one of his worst ever live experiences, he recounts in his autobiography, and in other interviews.

I was extremely underemployed. What can I tell you? It was eight musicians all playing the same. There’s no need for eight people. So, if the music requires just a little bit of icing on the cake from me, then that’s what it gets. There’s nothing else I can do. If Alan [White] is going to do what Alan does, which is very fine and well and good, there’s no need for two of us really. So, I adopted the role of an electronic percussion player.

It was totally out of the hands of the musicians involved. It was put together by political people from record companies – people who stand to make more money than the musicians do. They’ll put together a scenario and say “Hey, let’s go on tour for four months, make an album, bumpity bum bum bum. We, namely the politicians, will make a little bit more money than you will, but you will be able to make money and pay off all those debts you’ve got yourself into.” On the whole, this is what happens in rock. Most musicians operate from a loss-making position and they incur so much debt that they have to go on tour to pay off the debt. I exclude myself from this. Myself, I’m different. I don’t have to go on tour to do that kind of stuff. I could simply take the money, make a lot of money and use it on other things that I want to do. (Innerviews, Ibid.)

Yes in context

If these views seem harsh (though not, in my view, at all unfair), remember that this is the same Bill Bruford who, on 3rd August 2018, graciously came to unveil a plaque marking the formation of Yes in rehearsal at the Lucky Horseshoe (now Wildwood restaurant and bar). Likewise, he had previously given a generous and gently humorous introduction to the current incarnation of the group just before their 50th anniversary concert at the London Palladium on 25th March that year, describing them as “a wonderful band”. So there is a warmth towards his old flames there, too. But at the same time, in his autobiography, Bruford observes that rarely a day goes by without some piece of post arriving in relation to Yes’s financial or legal affairs, which were often chaotic and fraught. This is therefore an affection tempered both by musical realism and by not-infrequent reminders of past frustrations.

Bill Bruford has additionally enjoyed – if that is the word – a curious relationship with ‘Yes fandom’, it seems to me. On one level he is both grateful for, and a little bemused by, the adulation he has received, and the fact that without a buying public (of which Yes loyalists are a not insignificant part) large chunks of his musical journey would have been much more difficult. On the other hand, he once remarked in passing – after an Earthworks concert in Wales – that he finds the autograph-chasing, ‘selfie’ phenomenon rather odd, and there have been a number of instances when a slight air of irritation or confusion has surfaced in him as audience members at a jazz gig have called out (jokingly, no doubt) for “Roundabout” as an encore. This in turn feeds into frustration at the “too rock for jazzers, too jazz for rockers” pigeonholing.

At the plaque event, one member of the audience ventured the view that Bruford was, in words to this effect, “the best drummer in the world”. The recipient of this not unusual (in rock circles) complement smiled kindly, and observed wryly that he was “entitled to that opinion.” What he didn’t say was that he agreed, of course. What he might well have noted, in blunter vein, is that such comments often speak volumes about all the drum and percussion greats the complement-purveyor has not listened to, most certainly in the jazz world. ‘Best’ and ‘greatest’ are not, as Frank Zappa once noted, musical categories. The problem with them is not just that they are subjective (which summonses a longer story about how we make judgements concerning musical quality), but that they speak of our limited purview. And by ‘our’, I include my own.

Leaving prog for jazz

In truth, few progressive rock aficionados followed Bruford to the jazz side, but those who have can never look back. Some now regard rock as another country and a youthful dalliance. Others (like me, I guess) still find pleasure in some of those old haunts – I would scarcely have written a book about Yes if the band hadn’t remained important to me, in a curious way – while mostly living in musical environments far removed from the 1970s and from rock-based musics which still have those bands as a reference point. My own take would be that the ‘progressive impulse’ in rock largely migrated elsewhere: either beyond the rock field altogether, or into post-rock, experimental and hybrid musics, or sometimes into elements of the mainstream such as Radiohead.

Which leaves us with jazz as the context in which Bill Bruford started (in the aspirational sense) and finished his career. It is not quite accurate, in my estimation, to describe him as “a jazz drummer who ended up in a rock band” with Yes. He was a jazz lover, for sure. But he never attended music school, and his technique and attitude were partly self-taught, partly tutored (Lou Pocock of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra is often referenced, though with little detail) and very largely peer-developed. He learned, as he has often observed, by moving forward in playing with better and better musicians. Yes has always had decent musicians in it, but mostly (perhaps with the exception of the eccentrically brilliant Patrick Moraz, with whom Bruford formed a brief collaboration later on) of a certain kind and temperament. In Earthworks, he was able to recruit hot prospects and first-class talents (such Django Bates, Iain Ballamy and Steve Hamilton, and latterly Gwilym Simcock and Tim Garland) who could read proficiently, play absolutely anything very quickly, master complexities way past the pay-grade of most rock musicians, and operate both incredibly adaptably and with few resources. These worlds are night and day – musically, financially and culturally.

There are what could be described as ‘jazzy moments’ in early Yes, though they are fairly surface level. Peter Banks later developed much more of an interest in improvising, and there was an element of extemporisation in early Yes live performance (on borrowed tunes such as “In the Midnight Hour”). But when I asked Bill, during the Q&A at the aforementioned plaque unveiling, whether he had ever tried to encourage Yes down this route, he replied that it was just not within their style or instinct. Chris Squire, for sure, never played an unplanned note if he could help it – and Jon Anderson’s priority was song writing and the song form. Steve Howe, to whom Bill Bruford has remained close over the years, brought many jazz influences to the band in his playing, but less so in his arrangements and compositions. Rick Wakeman has barely a jazz bone in his body. So Bruford’s eventual departure from Yes (“a sunny, diatonic, A-major kind of band”) to King Crimson (“a dirtier, playing band”) was not only entirely logical but virtually inevitable.

Crimson – darker, freer, more complex and more experimental than Yes (other than in a few places in the early ’70s), provided something of a musical bridge for Bruford at various points in his timeline, along with his eponymous band (“clever instrumental rock, with a jazz edge”). But no-one familiar with the giants and stylistic variants of the jazz canon would listen to Bill’s playing, either in a progressive rock setting or even in Earthworks, and say, in any uncomplicated way, that he was a “jazz drummer”. Indeed, it is a complement to the man to recognise that he is far more difficult to compartmentalise that. In rock terms he is multi-faceted and precise, rather than heavy, with his distinctive snare sound (developed positively out of a technical weakness) helping him to cut through the mix without ever needing to sound too ‘loud’. In jazz terms, he may lack the loose-limbed ease and textural touch of a Bill Stewart, say. What he brings is precision, complexity, layers of ideas, and a rich palette of sounds which are, in some ways, as much resonant of the contemporary classical world as they are of jazz, world musics, and the more interesting areas of rock. Bruford therefore remained his own man throughout his performing life, and deserves to be recognised in that way.

In the end, jazz

Nevertheless, jazz is most certainly the foundation of Bill Bruford’s musical outlook and investments. But what is jazz? One can reference Miles, Coltrane, all the greats, and indeed a vast roster of drummers who leave many rock thumpers looking like floundering amateurs. But in the end, in addition to its deep roots in Black music and its many stylistic branches and detours, jazz is an attitude. This is why Miles despised the word when it was used as a box. How I would put it is that if rock is painting-by-numbers, jazz is Picasso… shapes, forms, ideas, experiments and possibilities which stretch the imagination and move well beyond established codes and forms. That isn’t to say that there aren’t distinct jazz habits, customs, idioms and inflections. Of course there are. But in the end, contemporary jazz – what we are hearing now, whenever now is or was – is always willing to lose itself in order to be able to find itself anew. This is where Bruford’s heart lies. Not in pleasing the crowds, nostalgia, “vocal entertainment” (how he described early Yes), big money and big stadiums. But rather in small, crowded spaces far from the mainstream, where groups of underfunded and often impoverished musicians ply a trade for the sake of art… and because they feel they have to, not because an accountant or audience number-counter cares. That has been what Bill Bruford seems to have most longed for throughout his career, tempered by the comfort and privilege, as he once neatly put it, “of being able to operate with bands where you can play in 17/18 and still stay in decent hotels.”

Returning to the source

As a footnote, I should add that I am a wee bit traumatised at the thought of people who love music not knowing about, or listening to, jazz. To me that would be like permanently having only 9 letters in the alphabet, or only three colours to paint with. The same applies with regard to classical music, of course. And electronica, and experimental sounds of many uncategorisable kinds. So while I can still enjoy rock-based music (and celebrate the strange genius of a Fripp or a Zappa, in particular), and while Yes will always be close to my soul, rock’n’roll per se often feels stiflingly limited, unimaginative and unsatisfying without the input, cross-fertilisation and challenge of other musics. That is partly what the ‘progressive’ story is about, of course, By the same token, while the histories of jazz and the variety of ‘classical’ eras and styles are unendingly rich in their own right, I cannot imagine being limited to those diets alone either (though they would provide much richer fare). Fortunately, these days, we do not have to be so constrained. Instead, the problems lie elsewhere – too much music, arguably; not enough operating/surviving money for the most creative and interesting performers and writers; the turgid influence of a technology that was supposed to liberate (over-sequencing everything, quantisation, instrumental deskilling, autotune, and the like).

But those are whole other issues. In the meantime, we should be grateful to people like Bill Bruford: for his time in Yes, for leaving Yes, for Earthworks, and for so much more. This week, the good souls of Yes Music Podcast (whose episode 438 provoked this article) are listening to the fabulous ‘Stamping Ground (Live)’ from 1994, which they will review in episode 440. I hope it opens up new vistas of listening experience and appreciation, as good music always should. And if you’re reading this and haven’t bought ‘Earthworks Complete’ yet – it’s worth its weight in credit cards, I promise. An astonishing musical treat.

But those are whole other issues. In the meantime, we should be grateful to people like Bill Bruford: for his time in Yes, for leaving Yes, for Earthworks, and for so much more. This week, the good souls of Yes Music Podcast (whose episode 438 provoked this article) are listening to the fabulous ‘Stamping Ground (Live)’ from 1994, which they will review in episode 440. I hope it opens up new vistas of listening experience and appreciation, as good music always should. And if you’re reading this and haven’t bought ‘Earthworks Complete’ yet – it’s worth its weight in credit cards, I promise. An astonishing musical treat.

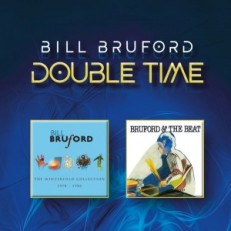

Image and related acknowledgments: album and book covers, the publishers. Other pics c/o billbruford.com, with specific credits under each photo – with grateful thanks. The BB quotations are from Innerviews, one of the most valuable hybrid music sources around. See also the accompanying book by Anil Prasad, Innerviews: Extraordinary Conversations with Extraordinary Musicians (Abstract Logix Books, Carly, NC, USA, 2010). The Yes plaque unveiling, mentioned above, was organised by Dave Watkinson in association with Yesworld. The official Bill Bruford and Earthworks website, which provides many imaginative reading and shopping opportunities, can be found here. His latest book is Uncharted: Creativity and the Expert Drummer (University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2018). The 1985 DVD (recorded in 1985), ‘Bruford and the Beat’, from which this article takes its punning subtitle, is now available as part of the CD/DVD collection, ‘Double Time’, which also includes a Winterfold Collection CD.

If you enjoyed this article, please see my book Solid Mental Grace: Listening to the Music of Yes (Cultured Llama Publishing, 2018).

Thank you for the article. Bill Bruford is my favorite drummer, so I happily feed on anything about him I can find. Just one correction: Bill’s “Five Percent for Nothing” track was on Fragile. Thank you again for the article.

LikeLike

Hi Kevin – good to hear from you. Yup, that mistake corrected… no idea what my brain did there!

LikeLike